Newsroom

Celebrating women and girls in science: A one-on-one with Dr. Freda Miller

February 11, 2025 marks the 10th annual International Day of Women and Girls in Science. Proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly, this day celebrates the importance of diversity in research, and acknowledges that “full and equal access to and participation in science, technology and innovation for women and girls of all ages is imperative for achieving gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.”

Dr. Freda Miller

Dr. Freda Miller (she/her) is a professor with both the Michael Smith Laboratories (MSL) and the Department of Medical Genetics. She also currently holds the position of Deputy Director with the MSL. Her research program explores the intersection of neuroscience and stem cells, with the goal of finding new approaches to promote brain repair in neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders.

In recognition of this date of significance, we spoke with Dr. Miller about her experiences in research, mentorship and leadership, and what advice she has for young women in science.

What did your journey to becoming a researcher and faculty member look like?

For me, a lot of it was kind of accidental. I always thought I would be a writer, but then in high school I had really inspiring chemistry teacher who encouraged us to experiment with new things, and that’s where I really caught fire for science. From there, it was just one step at a time. I never had an ambition to be a professor or a scientist, I just wanted to do something I found interesting, and at each step I kept re-evaluating and trying what came next.

How did you end up in your area of research specifically?

In my graduate studies I was focused on biophysics and molecular biology, attending meetings on the subject that at the time were almost completely men. I liked the field, but it felt very divorced from the reality of the world we see around us. At the same time, I was working on the same floor as several neuroscientists and developmental biologists, and was exposed, almost through osmosis, to those areas. When I was considering where to do my postdoctoral fellowship, I had a colleague encourage me to move into neuroscience, as the field was starting to use biochemical techniques to study the brain. That’s how I first launched into this fascinating field.

The second area I work in, stem cells, came later on. I thought that, perhaps if we can understand how stem cells build the brain, then we can try to come up with strategies for repairing the injured brain. I was very fortunate that at that time the Stem Cell Network was being established, and I was recruited right as my lab started working in that area. It led me to a community of Canadian scientists that really opened my eyes to things I didn’t know anything about.

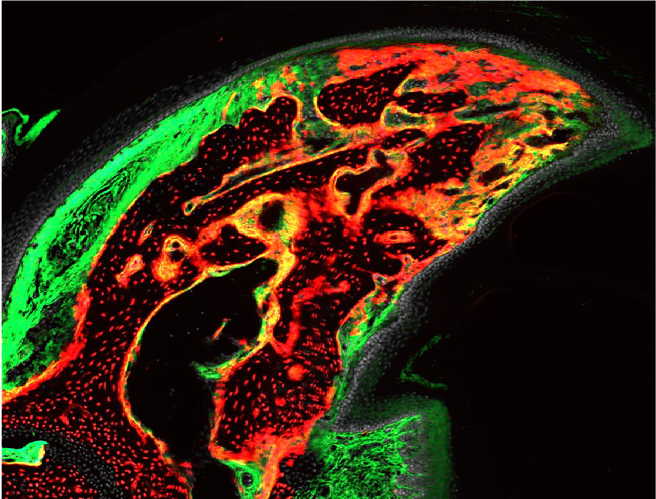

From Dr. Freda Miller’s research, pictured is a section of a regenerated mouse digit tip. Red shows tissue regenerated from cells originally from the bone, and green shows mesenchymal tissues.

Did you face any challenges or barriers on your academic journey?

I think a lot about the question of barriers and challenges, because that means different things to different people. I had two children, but I didn’t really view that as a challenge in the classical sense. I just viewed it as part of life, and I think it actually helped me to disengage from my work, which can be critical as it allows you to take a step back and look at research questions from a new perspective. Even though it was challenging to be a working parent, that’s common to many, many people.

In retrospect, even though I wasn’t aware of it at the time, I do think I was at a disadvantage because I didn’t have connections with scientists, academics, or even other professionals to start. As a result of that, I don’t think I really understood what I was getting into along the way. If I had been better prepared, I don’t think I would have gone through as many soul-searching moments, asking, “what am I doing here?”

How do you approach mentorship in the lab? How do you support your trainees?

I have a very different approach for graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, because I believe their needs are very different.

I think graduate students, particularly for their first few years, need a huge amount of guidance in more basic things like practical lab work and asking scientific questions. I also think on a more personal level that, at that time of life, a lot of people are doing some soul searching and wondering if this is really the right path for them. This is something I like to discuss with my students, trying to be encouraging when they’re struggling, while also reminding them that it isn’t a failure if they decide this isn’t for them. I teach taekwondo to the people in my lab, and one of the main reasons is so that students can feel more comfortable approaching me with these more personal things.

Postdocs are quite different, as they have a lot of basic training already, and have already gone through some soul searching. One important, pragmatic thing I need to support them with is guaranteeing publications, to open doors for moving forward in academia or industry. I also find it important to help them learn how to ask the right questions, giving them space to take a step back and say, “what do I find as the most interesting questions in this very broad area?” It’s important to find a sweet spot between a big-picture question that isn’t feasible, and smaller questions that don’t address a big enough picture. Finally, I really encourage my postdocs to not be afraid to learn new things, suggesting they audit courses, attend conferences, and present their work wherever possible.

Outside of being a mentor and leader in the lab, what leadership roles have you held, and what have you enjoyed most about them?

I’m currently the Deputy Director of the MSL, and I enjoy it because it’s a small, friendly community where I think many of us have similar objectives. From this small size, it feels like you get to actually meet everybody, which is important to me.

I have also held many other kinds of leadership roles over my career, and I have to say that the ones I have found most enjoyable and that I value the most are where it’s truly scientific leadership. I’ve led a lot of teams where we’re trying to get group grant funding to pursue big research projects, often under a larger umbrella like the Stem Cell Network or across groups at a university. While it takes a lot of organizational skill, it’s focused on what I’ve always viewed as more my forte, which is really the research.

What do you love most about your work?

I love the voyage of discovery, having the chance to ask about things we don’t understand and enacting plans to answer those questions. I enjoy looking at data in an open-minded way and saying, “what does this tell us that we didn’t know?” In science, you often have all these beautiful, intellectual constructs fuelling hypotheses and predictions, but often the result is surprising, and I really enjoy both stages of that.

Another one of the greatest gifts of pursuing an academic career has been having the chance to be surrounded by a community of idealistic people who are trying to make a difference.

What advice do you have for young women interested in pursuing careers in research and academia?

More pragmatically, the most important piece of advice I have is to check out the lab you are thinking of joining. This can be life or death when it comes to an academic career, because if you go to a lab that doesn’t fit with you, your personality, your goals, and the supports you need, it won’t set you up for success. I think it’s a scary thing to a lot of people, the idea that you are interviewing the lab as much as they are interviewing you, but this is extremely important.

I also think it’s important to not be afraid to take risks. Something I’ve said many times before is that the best way to decide whether you should do something is to ask, “will I regret it if I don’t?” If the answer is yes, you should go for it. The flip side of this is not being afraid to fail. There’s no shame in trying something and not being an expert at it in the end. A lot of people in science are perfectionists, but science is about imperfection, so don’t be too hard on yourself.

Finally, I think it’s important to figure out what kind of a scientist you want to be, and be that scientist. It’s not one size fits all, so take the time to get to know yourself and take advantage of your strengths as you move forward in your career.